Five years ago, I had the opportunity to publish Jennifer Reeser’s poems in the inaugural issue of Life and legends. That was my first introduction to Jennifer Reeser and her poetry. And although her name did not bear any particular identity, other than her being an American, whose ancestors might have come on the May Flower or through some other channels at some point in America, there was much more to her, that felt ancient and indicative of her deep connection with the American soil.

Of course, my observations were based on reading her books and the conversations we had via emails and on social media, but the “knowing” perhaps came from my own yearning to connect with the soul of Native America, which was somewhere preserved in the atoms of Reeser’s own body, spirit and poetry.

The poems of ‘Indigenous’ that have inspired this interview are the footprints of America’s soul, which has journeyed from the native trails to the pages of Reeser’s sixth poetry collection. These poems aren’t just an effort to trace her roots and rendition of native wisdom in a modern language, but they are also the silent protests and prayers of those who now live in the shadows, eclipsed in their own land.

In this interview, we explore Jennifer Reeser’s journey to her native roots and her poetry, with a special focus on “Indigenous’ (published by Able Muse Press), that puts her name next to William Jay Smith, Simon J. Ortiz, Sherman Alexie, and Joy Harjo.

Kalpna Singh-Chitnis (KSC): Congratulations on publishing Indigenous, another feather in your crown. Indigenous is an extraordinary collection of poems, giving a unique voice to Native American poetry in American literature. Tell us, what inspired you to write Indigenous poems?

Jennifer Reeser (JR): Thank you so much. Several years ago, the last of my mother’s American Indian family passed away, and I was left the sole local heir as executor, having to handle multiple estates. They had been those who raised me. As I began to sift through the decades of belongings, the family photos, the heirlooms, the “touchstones” of my past, the poems simply began to flood over me, demanding to be transcribed. It was time all this must be told.

When I was young, my grandparents were great friends with some Cherokees in another part of the state. Their indigenous heritage is well-known. They are locally famous Natives, who have been historically ridiculed as “redbones,” a derogatory term here in Louisiana, hurled at mixed-breed Native Americans. Early in their marriage, my mother warned my father that we were not EVER to mention Indian blood, because of that, because of the ridicule and shame. I have family in Indian Country, Tulsa, Oklahoma, which also was once my home. They are “out,” openly native, part of the Cherokee Nation. Likewise, the Native Americans on my father’s side, living on the Plains, are extremely proud of our heritage, which has always been honored, with the histories, customs, and culture spoken aloud, handed down. There is no possibility of “shaming” the living there, and with the last of my mother’s family gone, there is no one any longer, like my mother, whose wishes I might dishonor by acknowledging and writing about these things now. The ban has been lifted from me, in a manner of speaking.

KSC: In his review of Indigenous, A.M. Juster has said, the poetry of Indigenous Americans is receiving its overdue attention. Are you satisfied with the response Indigenous has received? If not, what is the reason?

JR: The public response to my book has delighted me. As you mention, the poet and translator, A.M. Juster, wrote a generous review, published by the Claremont Institute. John Nichols published an astonishingly-insightful review of the book in Front Porch Republic, pulling out things which I was skeptical any reader would understand. Only a few days ago, the journal, “First Things,” included my collection on a list of “must-read” books, the best books of the year, written by the critic, John Wilson. The New York Times bestselling author, Linda Sue Park, has praised it, as well. Commercially speaking, apart from critical praise, “Indigenous” has also been on the Amazon bestsellers, in Native American Poetry.

KSC: What is the reason it took so long for the Native American writers to make their presence felt in American literature?

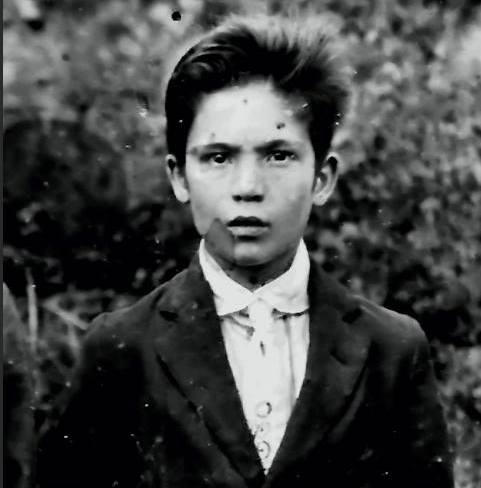

JR: There is no single reason, but a complexity of factors contributing to the slow emergence of Native American presence in literature. The most obvious, of course, is the reality that genocide has simply eliminated significant numbers of writers even eligible. When you further consider that among such a population, among many, there runs a resistance even now to assimilation, with those who refuse to participate in what they see as surrender to a thing known among us as “colonization.” You take, for example, one of the Cherokee shamans I translate, the medicine man who was called A-Yv-I-Ni, or “He Who Swims.” The man received death threats from others in his craft, who felt he was a traitor to the tribe, for co-operating with the White Man.

JR: There is no single reason, but a complexity of factors contributing to the slow emergence of Native American presence in literature. The most obvious, of course, is the reality that genocide has simply eliminated significant numbers of writers even eligible. When you further consider that among such a population, among many, there runs a resistance even now to assimilation, with those who refuse to participate in what they see as surrender to a thing known among us as “colonization.” You take, for example, one of the Cherokee shamans I translate, the medicine man who was called A-Yv-I-Ni, or “He Who Swims.” The man received death threats from others in his craft, who felt he was a traitor to the tribe, for co-operating with the White Man.

We are traditionally stoic and unemotional, reluctant to emote. Not once in my life did I ever see my mother cry. Lack of emotion is the kiss of death in poetry and the arts. This is one reason many filmmakers used to cast Italians and Hispanic actors in their Indian roles, rather than real Native American players, claiming that the former gave more, emotionally, to the performance.

Also, people do not realize the negative influence of non-Native writers who have greatly suppressed acceptance of Native American literature. Critical reaction to Longfellow’s “Hiawatha,” for example, was brutal. Writers as eminent as Lewis Carroll, the author of “Alice in Wonderland,” hopped on the populist bandwagon to mock this work, not only on a technical level, but for the very fact that it was Native American, in nature. The New York Times blatantly called Native American oral poetry and presence “monstrous,” unworthy of the English language, itself. The powerful, influential author of “The Wizard of Oz,” L. Frank Baum, published calls for a total holocaust of the American Indian, whose contributions he deemed utterly worthless.

It’s nearly impossible, as well as highly dangerous, to dare into a field where the leaders and heavyweights literally want you dead. People should not be shocked that it has taken us so long, and we have arrived so late to the game. People should be shocked that we made it here and this far, to play, at all. It continues to this day. My own publisher, Able Muse Press, received anonymous threats, warning not to publish “Indigenous.” According to them, abusive slurs were hurled at me, etc. One must be incredibly brave, and maybe even a bit crazy. We are still thrust into situations which are potentially-violent – and certainly destructive – just for existing.

KSC: Tell us about your Native background. How far the roots of your Native American ancestry go and other influences on your family descent.

JR: Forever; from antiquity, and the very beginnings of recorded history in what would come to be known as America. I am indigenous through both parents. The family may trace our first recorded Native ancestor to the spouse of my tenth great grandfather, a man born in Wales in 1615. He emigrated to America, took a Native American wife from the Powhatan tribe of Tsenacommacah, and became a trader with the natives. That is on my father’s side. Through my maternal line, my first recorded Amerindian ancestor was a Native American female who married my eighth great grandfather Spears, an immigrant born in 1639 in Northumberland, England. Since that time, Native Americans are present in every generation through six of all my eight great-grandparents. They occur more commonly and consistently across my line of ancestors than any of the white race or European ethnicity, which is basically English, with a trace of German.

Additionally, in nearly every instance of interracial marriage among my forebears, the union was between a white Englishman and a Native American woman. (I, myself, have an interracial marriage, to a white, German/French-American). Due to the fact that both sides of my lineage contain Europeans in this land since the early 1600’s,some of the Native Americans have, obliquely, attained a hazy place in recorded American history. I have written about some of these noble ancestors in “Indigenous,” and you will see more in the future, since I have not exhausted them, they are so many.

KSC: You are one of the very few American poets who have written poems on native themes and have also translated Native formulas into English. How do you view your own contribution different from the contributions of other Native writers and poets?

JR: The most evident difference is that I write in form. I write in meter and rhyme, whereas most do not, though a few deceased Native writers did in the past. The Cherokee formulas which I translate have not ever been put into the English language as literature, in the history of world literature. Nor am I aware of any Native writer who is doing so, at present. When you read these ancient Cherokee formulas in poetic form, you are reading something for the very first time, something which has never before been seen. Timothy Green, the editor of Rattle, said he believes my translation, “Formula for Frightening a Storm,” is the oldest poem that journal has ever published. Finally, these are works which are as genuinely American in origin as we will ever know, absolutely pure, from long before a time when the American Indian was irreversibly “tainted” by foreign influence. We were the first Americans, but we are no longer wholly what our ancestors were.

Beyond that, I am putting traditional Native American Indian and Cherokee history, culture, customs, legend, language, and modes of expression into traditional English and European formal vehicles, along with contemporary perspectives and current issues. As far as I know, this is not being done by anyone else, whether Native or non-Native. Being a half-blood, with centuries-old, half-blood heritage going back to the time of Shakespeare, this is my privilege and my birthright. I inhabit two worlds. I love both the native and the non-native.

Moreover, I am also involved continually in verbal and linguistic “foraging,” invention and experiments. For example, two poems in “Indigenous” are English poems, using those exclusive sounds available in the Cherokee language. This gives the reader a palpable experience of hearing a semblance of Cherokee, but with the additional benefit of English comprehension. Again, I am not aware of any Native writer doing anything like this.

KSC: How did you learn the Cherokee language? Does anyone in your family, besides you, speak a Native American language?

JR: My brother-in-law puts me to shame! He speaks numerous Native American Indian languages. His cousin is a former chief of the tribe, the first Cherokee chief ever to know both English and the Cherokee language. I learned Cherokee authoritatively, by the tribe’s head linguist, Dr. Durbin Feeling, who authored a brilliant Cherokee/English dictionary now considered the “Bible” of Cherokee linguistics. Another of my instructors was the late Sam Hider, Di-gah-doo-nah-I or Many Towns, whose first language was Cherokee. He was a minister and translator with Wycliffe. I have also audited classes taught by Ed Fields, a graduate of Northeastern State University, through the Cherokee Nation.

KSC: Are Native American languages dying? What kind of literature is being written in Native languages today?

JR: Native American languages are critically endangered. I remain hopeful for their survival, however, due to the excellent initiatives and programs such as the immersion school run by the Cherokee Nation, where students are exposed to the language early on, through the same method that they learned English as babies. A few years ago, I traveled north to visit family. While on the Cherokee reservation in North Carolina, a tribesman lamented to me the scant number of full-bloods left, who speak the native tongue fluently. It was dismal and sobering. But I am encouraged also by initiatives among business and in the private sector.

Five years ago, the Cherokee Nation finished its largest translation project in history, adding the language to Microsoft Office Web Apps, so that it can be used for PowerPoint, Word (which I use), Excel, and OneNote. Barring serious preservation efforts, many languages will be lost. But the Chickasaw, also, have an excellent program of instruction, even with a fun “television” series which portrays a well-to-do, modern family, conversing entirely in the native language, and is part of the Rosetta Stone program. So it seems that at least these are two examples which will survive, and even thrive.

To answer your second question, I can only speak of Cherokee. Years ago, there was a Cherokee novelist and poet by the name of Robert J. Conley. Conley wrote in the native language. His poetry was even part of the instruction I studied in the language, since it was translated by Dr. Durbin Feeling. I write in the language a bit, but don’t send it out for publication. The poet Timothy Murphy had heard Sioux spoken, but never Cherokee. I began making recordings of my own poems in Cherokee. I would send these recordings out to fellow poets, Rhina Espaillat, Bill Carpenter, Catherine Chandler, and Timothy Murphy. Apart from that – there just is not much market or audience for those. No demand, in my experience.

KSC: Who are your favorite Indigenous writers and poets?

JR: Simon Ortiz, Simon Ortiz, and Simon Ortiz. And then, there is Simon Ortiz. In the first of his readings I heard, he spoke of “leaving” as a cultural metaphor. My maternal grandfather’s last words began with, “I am leaving…” so Ortiz’s words went through me like arrows. The attachment was instantaneous, deep to the level of death, and as permanent, I think.

William Jay Smith, the first Native American poet chosen by the Library of Congress, prior to the office’s renaming as “United States Poet Laureate.” Charles Eastman. E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake). My inclinations are strange, substantially off the beaten path, outside the mainstream, and away from “celebrity” poets, for the most part. There are more, but you have never heard of them, nor have most readers. They have not won famous prizes, nor held “First Ever” appointments and such. Arcane Cherokees like John Ridge (Yellow Bird) and Ruth Margaret Muskrat, a truly marvelous talent born in 1897, who had the potential to rival Christina Rossetti. But just as her own voice began to crystallize, she abandoned poetry for activism. Otherwise, she would have developed into a major, major Native American Indian poet. She wrote “Sonnets from the Cherokee,” with a charming apology to Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

KSC: Recently you traveled to ancient native landmarks. What inspired your journey to these places? Are you writing anything else on the Native theme?

KSC: Recently you traveled to ancient native landmarks. What inspired your journey to these places? Are you writing anything else on the Native theme?

JR: One of my children took a spouse who is also part Native American, and moved to the Southwest, to be near that family and to attend the University of New Mexico. My husband and I decided to develop a closer relationship to that land, the territories of the Anasazi and Sinagua. I sojourned in the Sonoran Desert, explored and studied the prehistoric dwellings, sacred engravings, and at once fell in love. I will return, and write more.

This is nothing new for me. Years ago, my father took me on a “pilgrimage” to Cahokia Mounds in the Midwest, the place of his people probably built by my own ancestors. A resin replica of Cahokia’s sacred Birdman Tablet sits on the desk in my office, near my sample from the red dust of the ruins at Palatki. Furthermore, I live only hours away from Poverty Point, Louisiana, site of what we believe is the first tribal culture ever found in the United States. I have hiked, explored, studied, and written on each of these, with intentions to write even more. My poems of Cahokia appear in “Indigenous,” though the others are part of two other manuscripts, which I am not yet prepared to show a publisher.

KSC: From some of your social media posts, I have gathered that you have been often stopped by police and asked, you don’t seem to belong here. It is because of your mixed racial identity?

KSC: From some of your social media posts, I have gathered that you have been often stopped by police and asked, you don’t seem to belong here. It is because of your mixed racial identity?

JR: Only four years ago, my husband and I moved into our current neighborhood, which is predominantly white. No fewer than four police officers have stopped and questioned me since our arrival. Each time, I have been given the reason simply that I do not look like I belong here. One sheriff’s deputy, when I was only walking down the street in broad daylight, firmly instructed me to place myself against the back of the squad car, then suggested a ride out of the neighborhood. In a position to subdue and cuff me, I assume. On another occasion, the officer followed me on my customary walk around the park, then, as I arrived home, pulled across my driveway and parked, approaching and confronting me in my own carport. When I told this officer I was the homeowner, he kept repeating with clear disbelief, “You live here? You live here?”

Again, this is not new, however surprising it might be. During the days of desegregation, my dark father would be denied basic needs like fuel here, told, “We don’t serve your kind.” My maternal grandfather was called a “Damn Injun.” I have been told that this area was a stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan at one time. My husband and I met in Indian Country, Tulsa, Oklahoma, and began our marriage there, but it was necessary to relocate. Needless to say, nothing like this ever happened to me in Indian Country. I am hopeful it will blow over, once these residents realize I am in the vicinity, legally and legitimately, and that I pose no danger to the community.

The funny thing is, this is land which has been in my family for generations, which I inherited from my mother’s Indian family. So it has become a poignant metaphor for Native American displacement, from my perspective.

KSC: You know several languages and have translated the work of many renowned writers and poets. Please share your experiences as a translator. What language are you more comfortable translating from?

JR: I translate Russian literature. My translations of Akhmatova are authorized by her agents in Moscow. My most memorable translator’s experience is undoubtedly of the panel to which I was invited at the West Chester Poetry Conference. This was a meeting with a special envoy of Russians from Petersburg, Moscow, and elsewhere, headed by the American Professor Frank Reeve. Reeve was Robert Frost’s translator on his trip to Russia. He was also father to the late Christopher Reeve, the actor who portrayed Superman in the Hollywood movies. I made fine memories and friends there, which have endured to this day.

But Russian is not my most comfortable venue. I have the most ease with French, where I have translated primarily the poetry of Charles Baudelaire. Cherokee is off-the-charts difficult. It is truly a labor of love for me, an astonishingly sophisticated, precise, and unique language which global experts give the highest rating, in terms of toughness. When I translate Cherokee, I look like something straight from an Indiana Jones movie, my references and resources opened and spread around me, laser-beam intense in spectacles and archaeologist/scholar mode. My other European languages – the interest level is just not as high and those don’t “need” me in the literary sense. I am adding to my store of Native American tongues, which absolutely do need me. I am currently learning Navajo.

KSC: You frequently use Meter to write poetry. Writing poems in Meters is not an easy task. How do you do it so effortlessly?

JR: Apparently, I emerged from the womb with a knack for music. I have no other explanation. I am a trained musician, a percussionist schooled specifically in drum rhythms, and that is a plus, but even before that formal training, I was writing in rhyme and meter, from the age of eleven years old when I began seriously writing short stories, limericks, and other strictly measured, musical verse. The family lore goes that at the age of five, I stood atop the dining room table and recited “’Twas the Night Before Christmas” from start to finish. I was a military kid. My mother said as a toddler, I loved to stand near the window while the “warriors” passed on base, chanting their cadences along with them.

KSC: How do you decide to write a poem in Meter or free verse?

JR: Generally, a specific phrase or line comes to mind. I go with the phrase, letting it suggest the cadence to me, completely organic. But occasionally, I decide – I am going to practice the ballade form or whatever, and push it that direction.

KSC: Give us some tips for easily writing Meter poetry.

JR: The absolute best method is to read a lot of metrical poetry, and recite it often, aloud, so that it is visceral. It is no different than learning to speak a language. The more you hear it, the more you attempt it, yourself, the easier it becomes, and the more you will understand it. Memorize aids like Coleridge’s “Metrical Feet,” a fun way of combining the technical terms with their practical applications. Imitate good metrical poems of great authors, the way a child might mimic the adults. Be nonsensical, if necessary, not worrying about the meaning so much as the music. Once the structure is there, the meaning will come, like crows to rest.

KSC: Tell us about your other collections of poems. How did your journey as a poet begin?

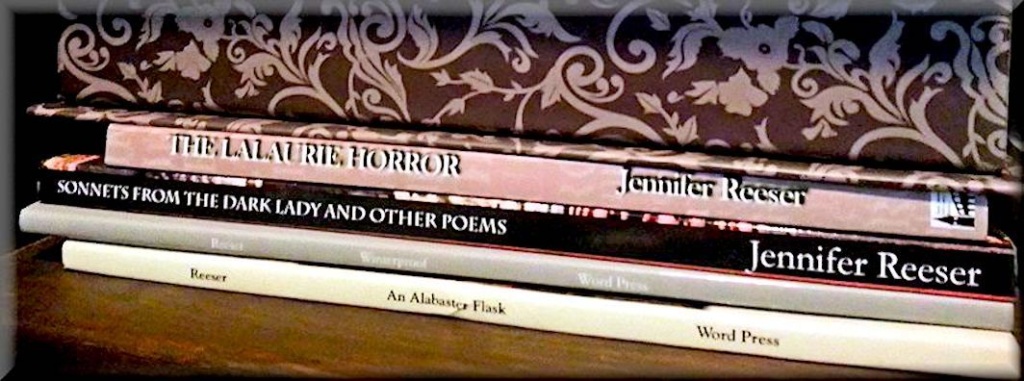

JR: I started writing with sustained intensity when I was eleven years old. I still have my notebook from that time, filled with juvenilia. Many respectable people kept me going. My debut, An Alabaster Flask, contains poems on various themes. In it, you can read the story of my father, who was given a special war mission to an archaic, native tribe in Viet Nam; also, many poems of Nature, birds, dragonflies, the earth; my ancestors. My second, Winterproof, builds on the first. My third revolves around a dialogue with William Shakespeare, in the voice of the Dark Lady of his sonnets. The Lalaurie Horror is a fantasy, a ghost story deriving from the historical account of Madame Lalaurie, an infamous and cruel slave owner of 19th century New Orleans. The book which preceded “Indigenous” was a collection of Baudelaire translations and poems about New Orleans, with many poems which sprang from time with my husband in an apartment in Paris, France. It is entitled, Fleur de Lis.

KSC: What inspires you to write?

JR: Almost everything.

KSC: What difficulties did you have to face in the early stage of your writing career? What advice do you have for new writers on writing and publishing?

JR: My biggest hurdles have been animosity and attacks from other poets, and the reality, as one literary “big-shot” confessed privately to me, “I can’t help you, because you don’t teach anywhere.” Writers outside academia must work much harder, with greater courage, strength, and endurance. But even those have proven trivial. My best advice is, never surrender. Perseverance is key.

KSC: How would you define American Poetry?

JR: I wouldn’t. I look for the universal in poetry. It would be better to leave to others, better qualified, such definitions.

KSC: How do you view diversity in American literature?

JR: Diversity is wonderful and to be enjoyed, so long as it reflects quality. No favors are done to any group, by promoting those who will represent us as weak or inferior.

KSC: How have American Politics influenced American Literature in recent years?

JR: I read very little political poetry or fiction, so I could not say. When I want politics, I read political analysts, scientists, and such. Experts and authorities trained in politics. I go to poetry and literature for something entirely other.

KSC: As a writer, do you consider yourself liberal or conservative?

JR: I am neither, but dead-center on the global political compass, a moderate balanced between libertarian/authoritarian, and liberal/conservative. Left wing writers have called me a fascist, while right wing writers have called me a communist. I take hits from both sides, as do all true centrists.

KSC: How do you view activism in literature?

JR: If its practitioner has a gift for it, skill with it, then why not? I’m not offended by “preaching,” in literature. A good sermon is a good sermon. Literature has the added attraction of being fictional, oftentimes, so we as writers can do things for a virtuous cause, which might in other fields be seen as unethical, or as an approval of evil. It’s one good way to be bad, if you will.

KSC: What are you writing next?

JR: I have no fewer than three books in the works right now. All of them in some way involve Native American Indian themes and content.

KSC: How do you want the world to remember Jennifer Reeser?

JR: I would like the world to remember me with love.

KSC: How do you view Life and Legends magazine?

JR: “Life and Legends” has astonished me from the very first issue. Its scope in content has always impressed me the most, its moral and ethical intelligence, but after that, the visual presentation never fails for beauty. It’s a highly professional production with heart. The combination is rare. You overlay that with a strong appreciation for diverse humanity and creation. It’s always seemed a holistic, sincere journal, with strong appeal for me. I hope to see it continue and prosper for a long, long time. Thank you so much.

*****

Kalpna Singh-Chitnis is an Indian-American Poet, Filmmaker and Editor-in-Chief of Life and Legends.

Kalpna Singh-Chitnis is an Indian-American Poet, Filmmaker and Editor-in-Chief of Life and Legends.

www.kalpnasinghchitnis.com

@AccessKalpna

I read this